Journey to St. Kilda – What I do for Puffins

Puffins in the Outer Hebrides

Journey to St. Kilda – What I do for Puffins

By Ethel DeMarr

As casual “birders”, or more specifically, as lovers of puffins, my husband and I had read that St. Kilda, off the west coast of Scotland, should be on our “bucket list”. Located fifty miles west of the Outer Hebrides, St. Kilda is considered a premier sea bird area, hosting the largest breeding colony of northern gannets in the world, along with puffins. To top it off, it is also a dual UNESCO World Heritage Site for both its cultural history and its natural beauty. The last residents of St. Kilda were evacuated in 1930, leaving a village that eerily still stands. The island is so remote and so difficult to reach, the government deemed it unsustainable. It is the most remote island in all of the British Isles. Where else would puffins hang out?

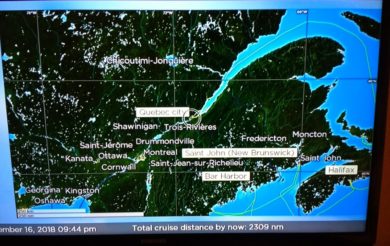

Just getting to the Outer Hebrides is no small feat. There are several options including flying. Given the weather in that part of the world, even in June, we dismissed that option immediately. That left ferries. One can take ferries from Oban or from Skye. Since we were traveling from southern Scotland, Oban seemed the best option for us. From the comfort of my desk in Arizona, a five-hour ferry ride did not seem so bad. Next time, we would make the shorter crossing from Uig on the island of Skye! Five hours on a ferry, in rolling swells and fog, was most unpleasant if you are not a seasoned sailor – which I am not!

Ethel and Terry DeMarr on Orca III

The next step is to find a tour company that will take you to St. Kilda. After reading some reviews on TripAdvisor and other travel sites, we chose Kilda Cruises on the isle of Harris. Angus Campbell and his family have a fine fleet of fast boats and a good schedule for visiting the island. Because of the uncertainty of the weather and because the fifty-mile trip is across some of the roughest water in all of Great Britain, Angus asks that you plan to spend at least a couple of days on Harris. In case of bad weather, if your scheduled trip cannot depart one day, it might be able to sail the next day. We decided to spend three nights on Harris near Leverburgh (as in Lever Brothers), South Harris, from where the cruises depart.

Otters Crossing

We ferried with our rental car from Oban to South Uist, then made our way to North Uist to catch the ferry to Harris. Once we arrived on Uist, we knew we were not in Kansas anymore! Rarely have we felt more remote. Sparsely populated, the islands are wild, flat and windswept. The “roads” are really single track lanes with wide spots every now and then called “passing places”. Occasionally, you might see a sign for “otter crossings” and often you need to dodge the sheep who seem to wander unfettered. And most signs are in Gaelic, as these islands have the largest population of Gaelic speakers in Scotland. When the sun shines, the long white sand beaches shimmer and the water is so blue you could think you were in the Caribbean. Standing stones, like mini Stonehenge, spot the landscape and remind us that man has been on these remote islands for millenniums.

Orca III Ferry

Early on the day of our departure, we drove to Leverburgh to meet Angus Campbell for our 8 AM voyage to St. Kilda. It was a cold, sunny and windy day. Angus confirmed that we were indeed “a go” for St. Kilda. Other tourists had gathered, all bundled up as if going on an arctic adventure. Everyone carried their packed lunches, as required and water proof clothing, just in case. Angus and his son David asked us to board the Orca III, a fifty-two foot catamaran, with an enclosed, well-appointed cabin. Although there was room for twelve passengers, there were only eight of us that morning. We were excited and optimistic with our comfortable seats, a full safety briefing and an obviously competent and caring crew. The fact that the voyage was three and three-quarters hours had not really registered.

Isle of Harris

It did not take long for the reality of our situation to reveal itself. Once we left the shelter of Leverburgh harbor, the wind and the waves assaulted the Orca III. As the color of my face began to turn green, David opined that it was a relatively calm day for the crossing. Really? Fortunately, the crew were prepared for land lovers like me and had provisions for our needs.

I will not attempt to describe seasickness beyond that. You get the picture. Suffice it to say, it was a long trip.

St Kilda to Village Bay

Finally, we neared the island and the little Village Bay where we would anchor. Once protected from the raucous sea swells, I was able to raise my head and behold a small bay and towering cliffs of green and grey rising up dramatically on either side. The sight was stunning! Perhaps the journey had been worth the suffering! I could see the stone village in the middle of this semi circular landscape and I was oh so ready to stand on dry land!

Welcome to St Kilda UNESCO Site

Boats cannot dock at the small pier so we anchored in the bay and took a zodiac to the island. We were glad we had donned our waterproofs as the zodiac offered no protection from chilly splashes. Once on land, we were greeted by a National Trust ranger who gave us a briefing and maps. We would have four hours to wander the island and explore the village. In addition to the National Trust wardens and volunteers, there is a military communications operation evident near the village with the island’s only vehicles.

St Kilda Main Street

I was disappointed to learn that we would not see any puffins on the island. We would have to wait until we returned to the boat and traveled to the giant sea rocks, the “stacks”, behind the island. So with diminished hopes of bird sightings, we set off to the village and its small museum. After a short uphill walk from the pier, we came to the main “street” of the village. The small stone dwellings, similar to crofter homes, seemed rather primitive even for the 1930s. One could imagine that just yesterday Angus or Ian were sitting in front of their house, chatting about the day’s hunting. I tried to imagine what it was like to be forced from your home. Life there may have been harsh but it was the only life they knew.

One house had been transformed into a museum explaining life on St. Kilda. Puffin lovers beware, the St. Kildans lived on sea birds and their eggs. Looking at tiny nooses in the display cabinet, I was disturbed to realize they were puffin nooses. And gannet eggs were a main staple of their diet. Of course, harvesting these delicacies required climbing up the ragged cliffs on the island’s edges. Only the strong and sure footed survived.

Above St. Kilda Village

From the village we began climbing up the slope away from the bay. There was no trail so we just scrambled cross-country. In this area we found the remains of the stone enclosures for sheep and several stone storage huts. While walking towards a stone corral, something large swooped down and hit me in the head! It was a skua or jaeger, a large seabird, similar to seagull. She was angry that I was near her nest. I was not injured but quite startled and anxious to be away from her! But she came at me again. This time I ducked in time, but the swoosh of her furious dive was frightening. We never saw the nest but we made note to avoid that general area!

Looking Towards the Stacks

At the top of the hill, we found ourselves on the edge of a steep cliff over looking the “stacks” and the sea behind St. Kilda. From this point, we could truly see and feel the rugged, remote nature of this tiny island and marvel that it had ever been inhabited! We recalled the story in the museum about the right of passage for young men on the island. They were required to make their own ropes for scaling these bare cliff faces to harvest the seabirds and their eggs. Unsuccessful rope makers were quickly removed from the gene pool!

From this vantage point we could see large numbers of sea gulls and gannets in the air and on the face of the cliff. The gulls seemed to be standing still as they soared in the high winds at the top of our precipice, sometimes just inches above our heads. Gannets demonstrated their aerial superiority as they stalked their prey from lofty heights then suddenly dove into the water. We could watch them all day. We enjoyed this spot for awhile, finally making use of our binoculars. However, even with our quality glasses, we could not see the puffins.

By now, it was time to return to the pier and to our boat. Our time on the island was at an end and we were finally going to see our little auk friends. My excitement was tempered as I thought of being back on the boat! Would I survive another three plus hours afloat? But there were puffins to see so I would survive!

Puffin Watching

Once aboard the boat, it was just a short trip to the “stacks”. We donned our rain gear in order to stand outside on the windy, wet deck for a better view. As we neared these towering craggy rocks, the puffins finally came into view! Their frantic flight is unmistakable. It is almost painful to watch them flap their stubby wings, as if they were not really intended to fly. And on land they are equally ungraceful, waddling like little painted clowns. Indeed, there were thousands of puffins, in the air and on the cliff faces. We sailed around the stacks awed by the size of these sea rocks and by the sheer numbers of sea birds. Although we were never close to the puffins, the sight of such large numbers was thrilling.

Fortunately, as we turned to begin the voyage home, exhaustion set in and I fell fast asleep to dream of this remote and unique place. Our journey to St. Kilda had been well worth the discomfort and the effort.

Read More of Ethel’s Travel Articles:

- Why I Love Scotland and the Kingdom of Fife

- Notes from Cornwall: National Trails and National Trust.

- Notes from Cornwall: Food and Random Thoughts.

- Notes from Africa: Visiting an Elephant Orphanage.